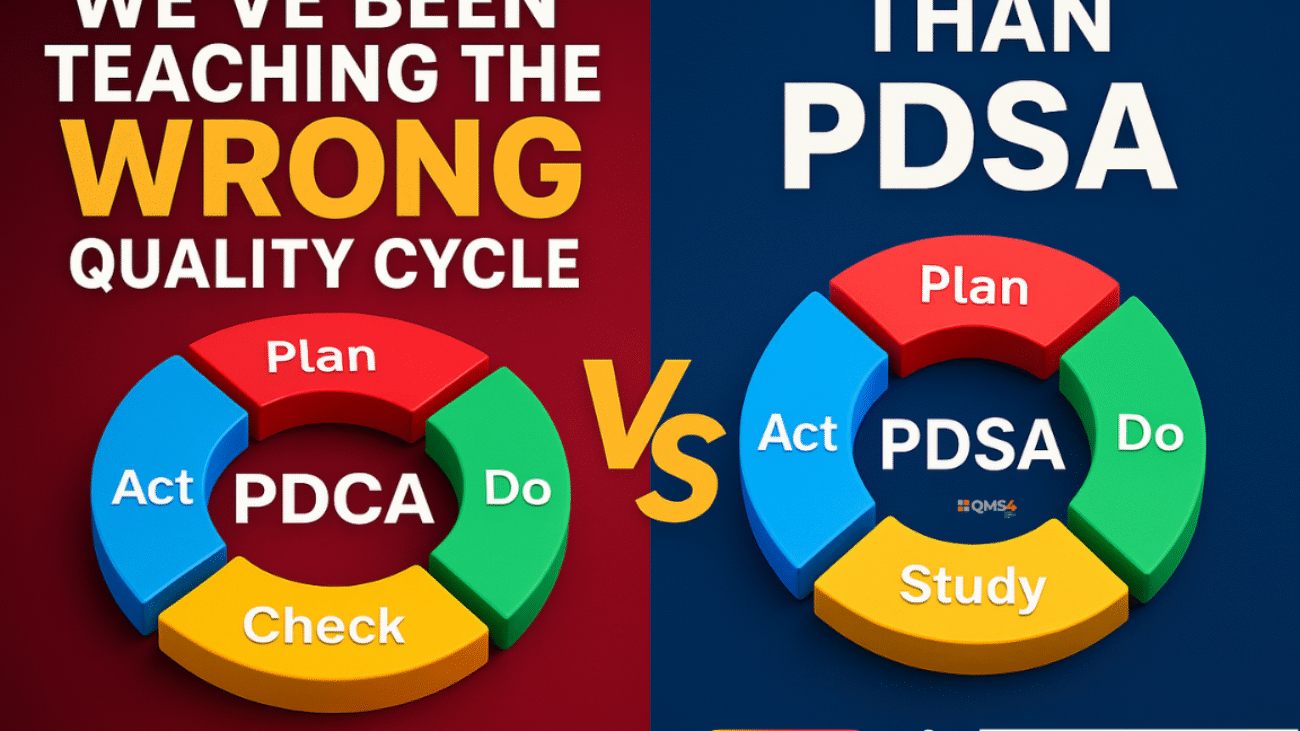

Most quality professionals are introduced to the concept of continuous improvement through a familiar four-letter cycle: PDCA—Plan, Do, Check, Act.

It appears in ISO standards, Lean handbooks, training courses, SOPs, and improvement posters in factories around the world.

Yet a surprising contradiction sits behind this global adoption:

W. Edwards Deming, whose teachings heavily influenced modern quality management, did not endorse PDCA.

Deming consistently promoted PDSA—Plan, Do, Study, Act, a version that emphasizes learning, analysis, and systemic understanding rather than inspection.

So how did the world end up championing a model that the original architect himself rejected?

To answer this, we need to look at the history, the culture of early industrial quality systems, and the behavioral implications of “Check” versus “Study.”

This article explores the origins, the divergence, and the impact of using PDCA instead of PDSA in modern quality systems.

1. The Origins: PDSA Started Before PDCA

The first known version of this cycle originated not with Deming, but with Walter A. Shewhart, Deming’s mentor.

Shewhart proposed the concept as a scientific process of iterative learning:

-

Specify the problem

-

Try a solution

-

Observe what happens

-

Reflect and adapt

Deming expanded Shewhart’s ideas into a structured cycle—Plan, Do, Study, Act—emphasizing:

-

experimentation

-

learning from variation

-

continual refinement

-

system-level understanding

“Study” was the heart of the model because Deming believed:

“Without study, there is no true improvement—only activity.”

His intention was clear: improvement requires more than checking compliance or pass/fail outcomes.

It requires understanding why the system behaves as it does. Here is the original article link – click here

2. How PDCA Became Popular in Japan — Without Deming’s Approval

During the 1950s, Deming worked extensively with Japanese industry through JUSE (Japanese Union of Scientists and Engineers).

Japanese manufacturers wanted a model that factory workers could quickly understand and apply on the shop floor.

They also needed a model that aligned with the cultural and operational realities of post-war production.

This is where the shift began.

JUSE adapted Deming’s PDSA cycle—not out of disagreement, but out of practicality.

In Japanese manufacturing culture at the time, inspection was the dominant understanding of quality.

So instead of “Study,” JUSE adopted the more familiar term “Check.”

This gave birth to the PDCA cycle:

-

Plan

-

Do

-

Check

-

Act

It was simple, familiar, and aligned with the Japanese focus on process verification.

But the adaptation carried a hidden cost:

It shifted the mindset from learning to inspection.

Deming repeatedly clarified that he did not endorse PDCA.

He felt “Check” implied passive evaluation rather than active learning.

In his later lectures, Deming stated:

“The ‘Check’ step does not encompass the idea of learning from data.

Study is the correct word.”

Despite this, PDCA had already gained remarkable traction in Japan.

3. Why PDCA Spread Globally While PDSA Didn’t

Once Japanese industry adopted PDCA, the model gained momentum—much faster and wider than PDSA ever had.

There are several key reasons for this:

3.1 PDCA Was Simpler and Easier to Teach

Trainers, consultants, and educators found PDCA:

-

easier to explain

-

easier to visualize

-

more intuitive for frontline workers

-

easier to scale across teams and sites

“Check” felt logical.

Everyone checks work.

Everyone checks results.

Everyone checks compliance.

By the time Deming clarified his preference for PDSA, the world had already standardized PDCA in training materials, textbooks, and ISO documentation.

3.2 PDCA Fit the “Inspection-Based” Quality Culture of the Era

Early industrial quality was heavily focused on:

-

post-production checks

-

conformance

-

pass/fail criteria

-

inspection points

-

defect detection

PDCA aligned naturally with that culture.

“Check” reinforced existing behavior.

By contrast, “Study” required:

-

analyzing variation

-

interpreting data

-

understanding cause-and-effect

-

reflecting on system behavior

These were more advanced capabilities that many organizations weren’t ready for.

3.3 ISO and Western Quality Systems Codified PDCA

When the global quality movement expanded during the 1980s and 1990s:

-

ISO 9001 adopted PDCA

-

Lean and early TQM programs adopted PDCA

-

Corporate training programs built PDCA into their materials

PDCA became an industry norm before PDSA could gain meaningful traction.

Once embedded into standards and certifications, it became extremely difficult to replace.

3.4 The Language Barrier Played a Role

The word “Study” in English conveys analysis and reflection.

But in many languages, “study” translates to formal education or academic activity.

“Check” was easier to translate and understand in operational contexts worldwide.

This linguistic simplicity helped PDCA scale exponentially.

4. Why Deming Strongly Preferred PDSA Over PDCA

Deming’s concerns with PDCA were not superficial.

His preference for PDSA was grounded in deep principles of:

-

systems thinking

-

statistical reasoning

-

behavioral science

-

learning and adaptation

The difference between “Check” and “Study” may seem small, but the mental models they create are profoundly different.

4.1 “Check” Reinforces an Inspection Mindset

When teams think in terms of “Check,” they tend to:

-

focus on compliance rather than learning

-

look for pass/fail results

-

treat data as static

-

evaluate outcomes rather than causes

-

default to surface-level conclusions

In many GMP and ISO environments, this shows up as:

-

checking whether CAPA was implemented

-

checking whether SOPs are followed

-

checking audit findings

-

checking training completion

This often leads to a procedural approach to quality—not an analytical one.

4.2 “Study” Promotes Learning and Understanding

“Study” forces teams to ask deeper questions:

-

What patterns appear in the data?

-

What variation is normal, and what is special?

-

What does this tell us about the system?

-

What behaviors influenced the outcome?

-

What assumptions were proven wrong?

This aligns with root cause analysis, statistical thinking, and continuous improvement.

For example:

-

studying why deviations occur

-

studying how work-as-done differs from work-as-imagined

-

studying human factors and behavior

-

studying systemic constraints

-

studying patterns over time rather than events in isolation

PDSA encourages organizations to understand the story behind the data, not just check the data itself.

4.3 PDSA Is More Compatible With Modern Quality Systems

Today, the most advanced quality methods are built around learning:

-

Lean A3 thinking

-

Six Sigma DMAIC

-

FDA’s Quality by Design

-

Human and organizational performance (HOP)

-

Risk-based thinking

-

Behavioral quality

-

Modern CAPA effectiveness principles

Each of these approaches requires thoughtful inquiry, not simple evaluation.

In fact, PDSA aligns almost perfectly with modern frameworks:

-

“Plan” = Define the system or problem

-

“Do” = Pilot the change

-

“Study” = Analyze impact and variation

-

“Act” = Standardize or adapt

This makes PDSA a more robust model for regulated industries like pharma, biotech, and food manufacturing.

5. Practical Impact: PDCA vs PDSA in Real Quality Systems

The choice between PDCA and PDSA is not merely academic.

It has practical consequences on how organizations handle:

-

deviations

-

investigations

-

CAPA

-

change control

-

process improvement

-

audit findings

-

risk management

PDCA often leads to:

-

superficial checks

-

limited analysis

-

confirmation bias

-

implementation-focused CAPA

-

lack of behavioral insight

-

repeated deviations

PDSA leads to:

-

deeper data-driven learning

-

identifying systemic and behavioral root causes

-

more effective CAPA

-

stronger preventive measures

-

long-term stability

This mirrors the shift in modern GMP expectations—from “prove compliance” to “demonstrate understanding.”

6. So Should We Stop Using PDCA Entirely?

Not necessarily.

PDCA is:

-

simple

-

easy to train

-

effective for basic improvement cycles

-

useful at the operator or team level

-

helpful for visual management and daily management

But for higher-level problem solving—especially in regulated or complex environments—PDCA falls short.

That’s why many organizations use PDCA for daily improvement and PDSA for analytical or strategic improvement.

A blended approach can work, as long as teams understand the philosophical difference.

7. Final Thought: A Small Word, A Big Mindset Shift

In quality management, terminology often seems minor.

But the shift from Check → Study represents a fundamental change in thinking.

Check asks: “Did we do it?”

Study asks: “What did we learn?”

Behind that difference lies the reason Deming spent decades correcting the world’s understanding of the cycle.

PDCA made quality easy to teach.

PDSA makes quality meaningful to practice.

Want more insights like this?

Connect with Lokman in LinkedIn| Subscribe to my Weekly Newsletter (Quality Career and GMP Insights) | Follow QMS4 | Visit: www.qms4.com