A Familiar Story in Quality

The deviation was raised at 6:14 PM.

A filling line operator had added a component in the wrong sequence—again. This wasn’t the first time it had happened on that line. Still, the supervisor followed protocol:

-

Deviation logged

-

Investigation opened

-

Root cause marked as “human error”

-

CAPA assigned: Retrain the operator

-

Batch released

A month later, the same deviation occurred—different operator, same mistake.

And once again, the cycle repeated.

This story isn’t from one facility—it echoes across hundreds. In pharma and life science plants worldwide, GMP compliance is chased like a moving target. But here’s the deeper issue: it’s not just the procedures—it’s the patterns. And those patterns begin with people.

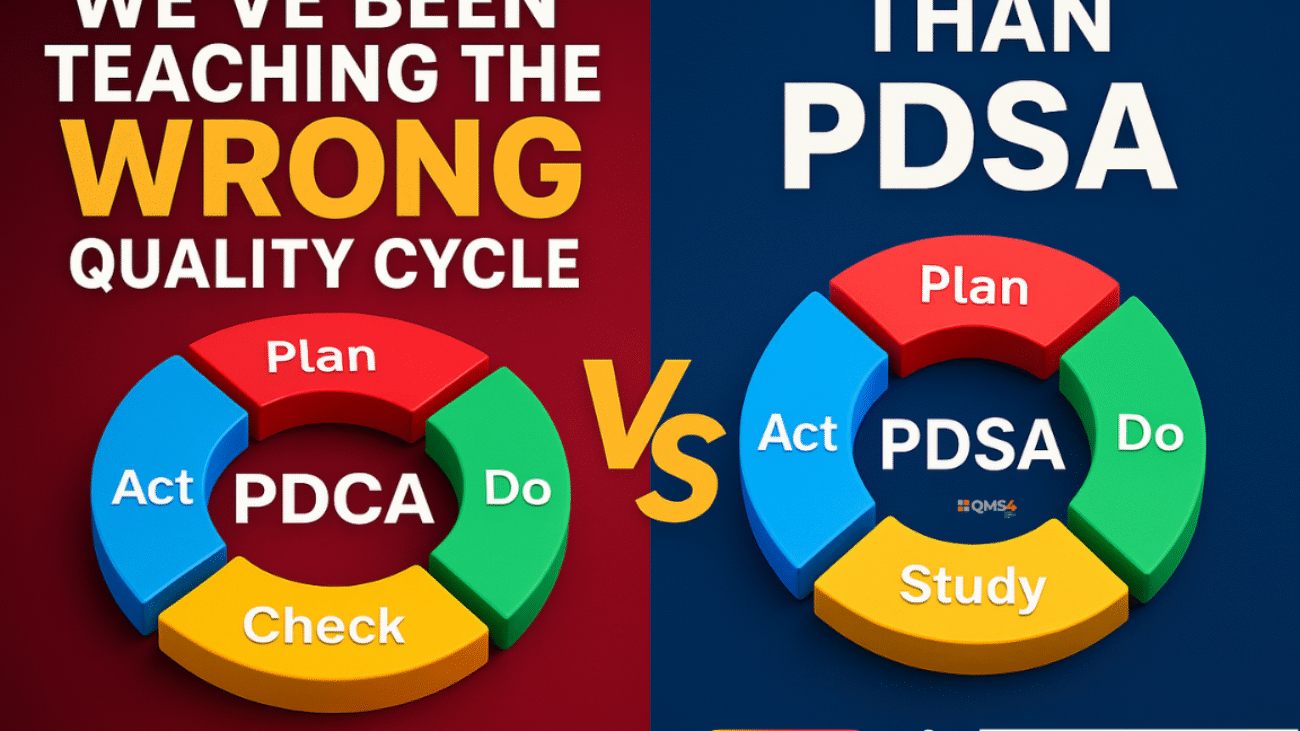

The Standard CAPA Cycle: A System Designed to Move On, Not Dig In

Most CAPA systems follow a familiar structure:

-

Identify the issue (Deviation, Audit finding, Complaint, etc.)

-

Investigate and determine the root cause

-

Implement corrective and preventive actions

-

Close the record

This approach is clean, auditable, and efficient. However, there’s a fundamental flaw.

This cycle is built for resolution, not transformation.

For example, in many facilities:

-

Root cause = Operator forgot or didn’t follow the SOP

-

Corrective action = Retrain the operator

-

Preventive action = Update the SOP or add a checklist

But what happens when:

-

The same operator repeats the mistake?

-

Another operator makes the same error?

-

The checklist is ignored under time pressure?

In those cases, the CAPA might close—but the risk quietly reopens.

Human Error: Convenient Label, Dangerous Assumption

When a deviation is marked as “human error,” it often signals three things:

-

A fast way to move the record forward

-

A protective shield for the system

-

A convenient label that ends the conversation

But human error is not a root cause. It’s just the beginning.

Instead of asking, “Who did it?”, we should ask:

“Why did it make sense to do it that way?”

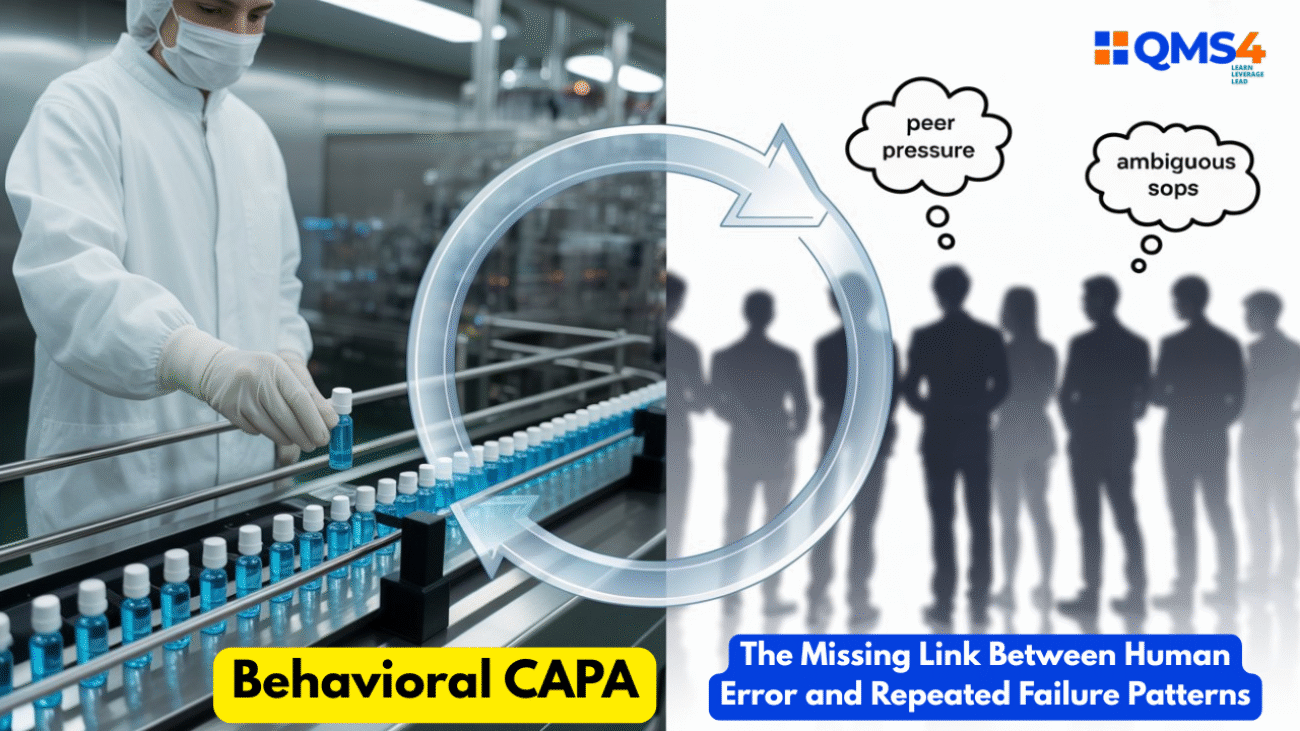

Introducing Behavioral CAPA: A Missing Link in Quality Systems

Behavioral CAPA doesn’t ignore human error. It investigates it.

It asks:

-

What behavioral patterns or team dynamics contributed to the event?

-

What cognitive biases were at play?

-

How did context shape decisions?

It examines:

-

Pressures and incentives

-

Organizational norms

-

The gap between formal policy and real-world behavior

Rather than assigning blame, it fuels curiosity. Instead of closing the file, it opens a mirror.

Case Example: The Unwritten Rule That Broke the SOP

At a sterile manufacturing site, an SOP required double verification before component addition. Yet staff skipped it—then logged it as complete.

The formal investigation listed “non-compliance”. But behavioral analysis revealed deeper truths:

-

Unrealistic production targets

-

Subtle supervisor pressure to “keep the line moving”

-

Peer normalization of shortcuts:

“We all do it—just don’t get caught.”

The CAPA? Retraining.

The real outcome? No change. Same issue returned next quarter.

What could Behavioral CAPA have done differently?

-

Assessed pressure from production KPIs

-

Redefined metrics to value quality, not just speed

-

Delivered team-based behavioral training

-

Fostered psychological safety to report unsafe norms

Why Patterns Repeat: Because We Fix Events, Not Systems

Quality systems are built around events:

-

One deviation

-

One complaint

-

One audit finding

But human behavior doesn’t work like that. It runs in patterns:

-

People shortcut when under pressure

-

Silence becomes survival when mistakes lead to punishment

-

Workarounds spread faster than policy updates

Traditional CAPA addresses the event. Behavioral CAPA addresses the environment that makes those events likely.

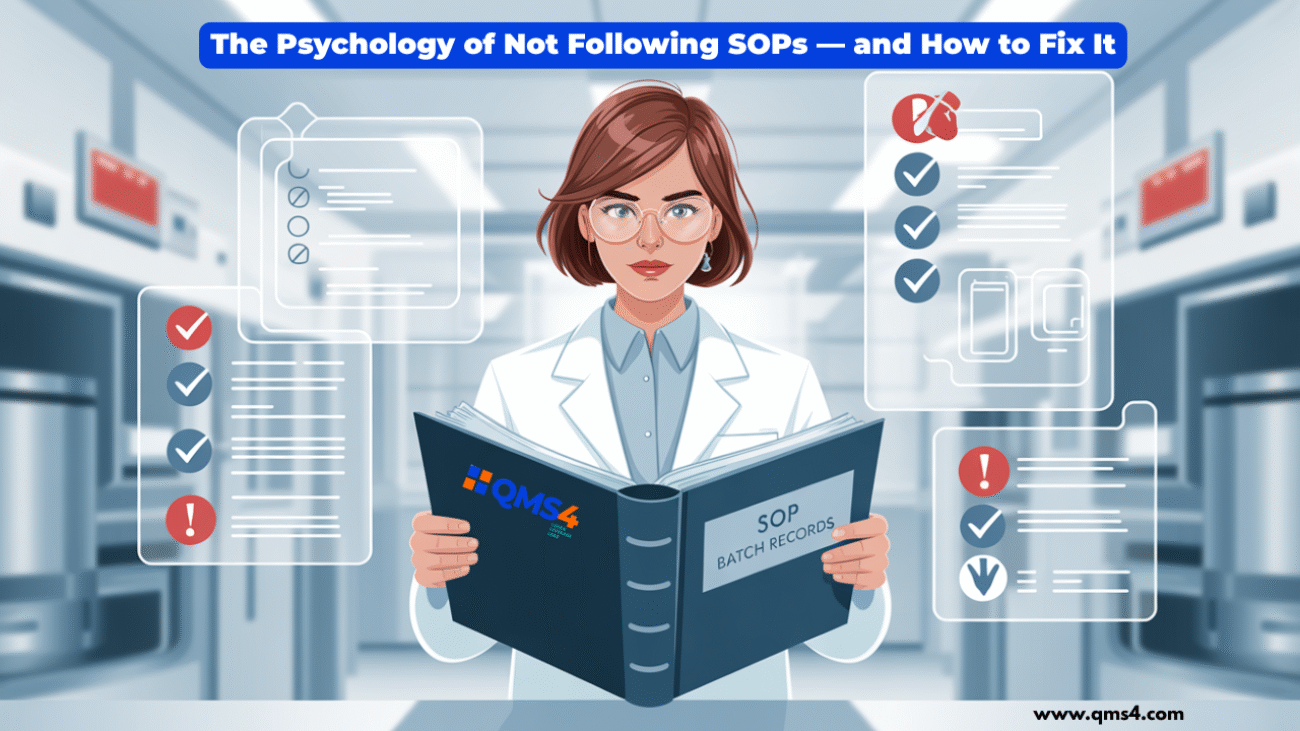

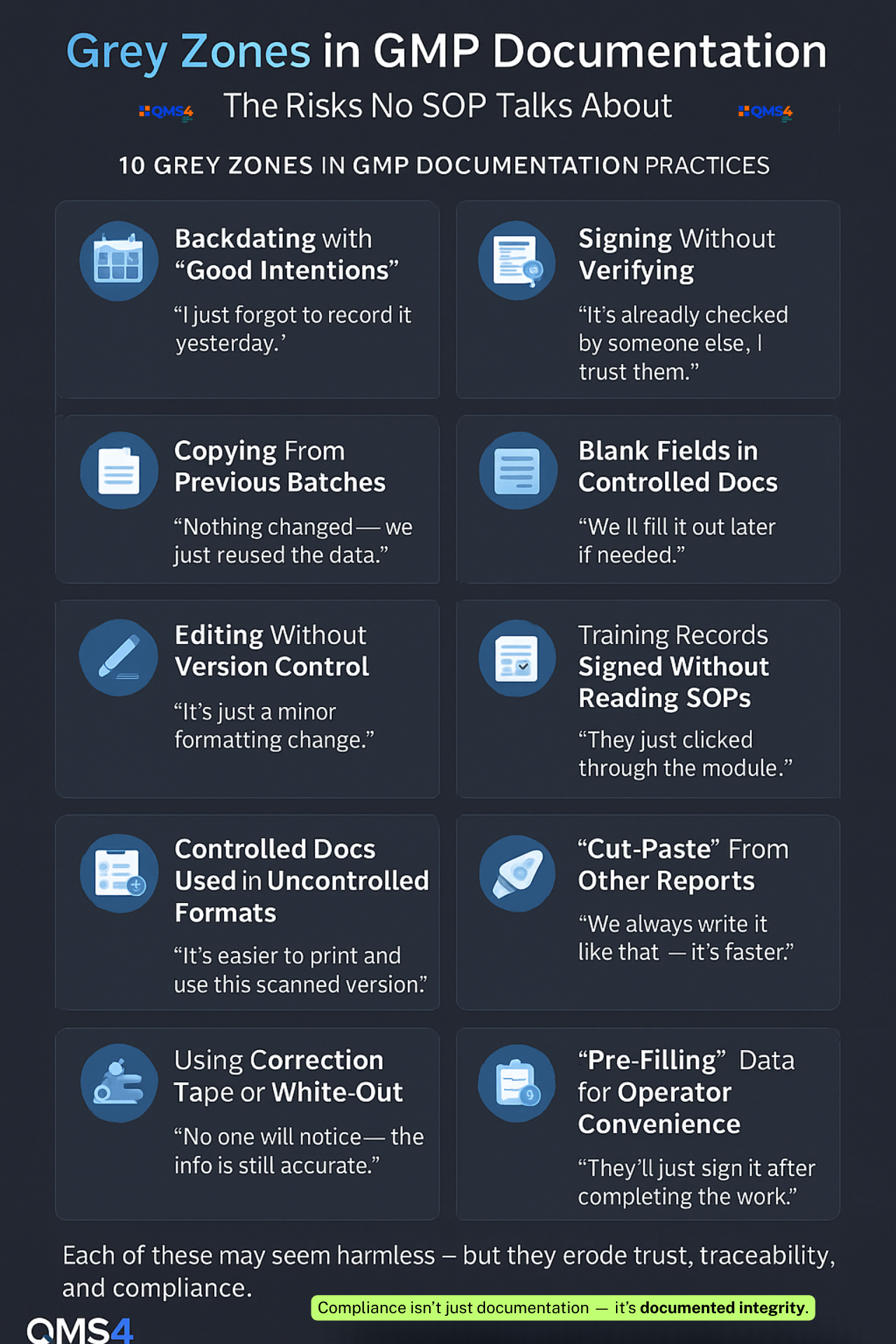

The Data Lie: Trends Don’t Show Truth Without Behavior

Your audit slide might proudly show:

-

✅ CAPAs closed in 30 days

-

✅ Recurrence rate reduced

-

✅ 100% training completion

But what if:

-

Staff rush through LMS modules without learning?

-

SOPs are signed under time pressure—without reading?

-

Investigations are templated and fear-driven?

These metrics provide a false sense of control.

Behavioral CAPA pushes deeper—beyond the numbers, into the behaviors they hide.

Behavioral Root Cause Categories: A Smarter Lens

Behavioral CAPA enhances—not replaces—your tools by layering in behavioral root causes:

| Category | Example Behavior |

|---|---|

| Time Pressure | Rushing checks during changeover |

| Group Norms | Following peers who bypass steps |

| Fear Culture | Hiding errors to avoid blame |

| Ambiguous SOPs | Interpreting unclear instructions |

| Learned Helplessness | “Reporting won’t change anything” |

| Overreliance on Memory | Forgetting steps in complex tasks |

| Poor Feedback Loops | Not hearing what happened post-deviation |

These categories unlock the “why” behind the repeated “what.”

Integrating Behavioral CAPA into Your QMS

Here’s how to get started:

1. Upgrade RCA Templates

Add behavioral prompts:

-

What made this behavior seem acceptable?

-

Was there peer pressure or incentive misalignment?

-

How common is this behavior—even when not reported?

2. Train Investigators in Behavioral Science

Equip QA teams and supervisors with skills to probe:

-

Context

-

Biases

-

Cultural norms

3. Map Behavior Loops

Use tools like:

-

Behavior mapping

-

Cause-and-effect charts with human factors

-

Peer interviews

4. Shift From Fixing to Rebuilding

Design CAPAs that:

-

Change the environment

-

Adjust expectations

-

Rewire feedback and communication

Not just tweak policies.

Behavioral CAPA in Action: A Pharma Case Study

Company: Mid-size injectable manufacturer in Southeast Asia

Problem: Repeated cleaning deviations (“missed spots,” “residue”)

Standard CAPA: Retraining + checklist updates

Behavioral CAPA Revealed:

-

Staff were trained—but rushed due to poor handovers

-

Supervisors discouraged reporting small misses

-

Employees feared blame for admitting mistakes

True Root Cause:

Fear culture + shift pressure

CAPA Redesign:

-

Introduced 5-minute shift buffers

-

Created open forums for mistake-sharing

-

Changed KPIs: from “cleaning time” to “cleaning quality”

Result:

🔻 70% drop in cleaning-related deviations over 6 months

Why This Matters: Behavioral CAPA Isn’t Just a Fix—It’s the Future

The industry is shifting:

-

Regulators now care about culture, not just checklists

-

Patients demand trust—not just timelines

-

Digital QMS systems automate workflows—but not wisdom

Behavioral CAPA isn’t optional. It’s essential.

It creates systems that understand people—not just procedures.

Reflective Takeaway

Next time you list “human error” in a deviation, pause.

Ask yourself:

-

What system allowed that behavior?

-

What pattern am I ignoring?

-

Will this fix break the cycle—or just delay the next incident?

Behavioral CAPA is not about assigning blame.

It’s about creating a system where the truth feels safe—and change feels possible.

Conclusion

Despite best intentions, many CAPA investigations fail because they stop at the surface. They treat symptoms, not causes. While procedural fixes may check audit boxes, the same deviations resurface—sometimes in new disguises. Why? Because behavior, culture, and mindset are rarely part of the root cause conversation.

Until we look beyond the incident—into why people act the way they do—we’ll keep cycling through CAPA loops that change nothing.

It’s time we stop blaming “human error” and start understanding it.

💬 What hidden behaviors have you seen quietly sabotage quality systems—yet never make it into the report?

👇 Share your story or insights in the comments—let’s break the silence around the real roots of CAPA failure—together.

Want more insights like this?

Connect with Lokman | Subscribe to my Weekly Newsletter (Quality Career and GMP Insights) | Follow QMS4 | Visit: www.qms4.com